On Thursday,

June 23, 1921, the Shell Oil Company struck oil at its well at Temple Avenue

and Hill Street, on Signal Hill. A new era was born, and a new city, Signal

Hill, came into being. The City of Signal

Hill has been built on oil, so has much of Long Beach, which has benefited from

wells drilled on its properties in the Signal Hill oil field. The Signal Hill oil field runs from northwest

to southwest, about five miles long by one mile across. In the northwest, the

field begins near the junction of the San Diego Freeway (I-405) and the Long

Beach Freeway (I-710) and roughly parallels the 405 freeway near the

intersection of Lakewood Boulevard and Pacific Coast highway at the traffic

circle. Portions of the field also extend into the Alamitos Heights area by

Recreation Park, and the Los Cerritos area of Long Beach, though these areas are

no longer productive.

|

| Source: Wikipedia |

Revenues from the oil industry

fuel the treasury in both cities, but what brought much wealth also has had

costs. There were numerous explosions,

fires and deaths in the oil fields. Only

a few of the tragedies have been remembered.

I’ve included three of the most well-known in this article, followed by

a chronological list of other reported accidents and deaths I’ve been able to

find in my research. As you will realize

when you see the list there were many.

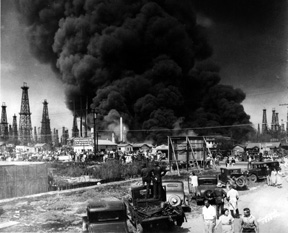

Fisher Fire

Fires, explosions and accidents

were common in the early days of Signal Hill oil. The newly formed city didn’t

have its own Fire Department until 1926 and had to rely on Long Beach for fire

protection. One of them was the 1924

Fisher fire which destroyed four derricks and two storage tanks about 8 a.m. on

July 15, 1924.

|

| Fisher fire, 1924. |

Wayne Fisher estimated total

damage at $100,000 ($14.3 million today).

By all accounts, the Los Angeles

Times reported, Mrs. Z. T. Nelson, Signal Hill’s mayor was the heroine of

the fire. Jessie Nelson organized and headed a relief committee to aid the 350

firefighters, saw to it that they were fed in shifts and personally passed

among them giving them encouragement.

The day’s most spectacular feat

was that of Alex Scott, one of the crew of the Foster wells. While fighting the

Fisher fire he saw the top of his own derrick burst into flames and climbed to

the top with a hose strapped to his back in sight of thousands of spectators. He

later received $100 for his bravery.

Fortunately there were no

deaths. The only casualty was Fred Harold who tripped and fell badly burning

his arm as a stream of blazing oil escaped from one of the oil tanks.

The cause of the explosion was

thought to have been caused by one of the burning derricks falling into the oil

tank, causing an instant explosion.

The story of well owner Walter

H. Fisher is similar to many who made a fortune on oil. Fisher and his family

arrived in Los Angeles with only $5. He opened an insurance business, and made

an early investment in oil, forming the General Petroleum Company. At the time of his death in June 1926 his

estimated worth was $5,000,000 ($69.2 million in today’s money).

Richfield

Oil Fire

Another disaster occurred 85

years ago on June 2, 1933. This time

it was an explosion at the Richfield Oil Company at Twenty-Seventh Street and

Lime Avenue which killed ten, and injured thirty-five.

|

| Richfield field ablaze, 1933. |

It was a horrible tragedy that

began with a tremendous refinery blast that was felt in cities thirty miles

away. The fire that followed reached two

homes, but the heroic efforts of 500 men, armed with shovels, prevented the oil

that flowed from broken storage vats from igniting and spreading the fire

further into residential areas. All in all fifty dwellings were damaged and a

dozen other small buildings destroyed.

One body taken to Seaside

Hospital was so mutilated staff could not tell if it was a man or woman. A belt buckle was all that helped identify

what was left of 34-year-old Robert Bennett, of 3056 East Second Street, whose

remains were pulled from beneath a pile of charred building Equipment numbers found

near other remains were traced back to those who had checked them out, allowing

for further identification. One of the

victims was Carl Robinson (226 ½ Covina Street), whose wife told local police

that the day of the blast had been the first work her husband had been able to obtain

in nine months.

materials the

following day.

|

| Richfield fire aftermath. |

Lottie Carlyon and her 8-year-old daughter

Marilyn were burned to death before firemen could get near enough to put out

the flames that engulfed their home. The

mother and the little girl had been knocked unconscious by the blast and were

unable to get out of the house before it caught fire. Ironically Lottie

Carlyon’s husband, Tom, was directing a crew of men in a derrick near his home

when the blast snuffed out the lives of his family. He was closer to the explosion than his wife

and daughter, but was able to stagger from the burning area before being

trapped by flames. The rest of the dead

were trapped inside the absorption plant when the blast flattened it.

Witnesses said there were

actually two explosions. The first, a

minor one, caused the second. The second

blast was so intense it wrecked homes and other structures within a radius of

several blocks and shattered plate glass windows thirty miles away. At first everyone thought another earthquake

had hit (the massive Long Beach Earthquake had occurred March 10, 1933), but

they quickly realized it was an explosion when an immense column of smoke and

flame shot skyward.

Five hundred firemen, police,

sailors, marines and volunteers fought for four hours to put out the fire which

razed an area of two city blocks.

Fifteen thousand spectators gathered to watch the inferno and the

thousands of barrels of crude oil which flowed through Long Beach streets like

a river.

A storage tank failure was ruled

as the cause of the explosion which was the worst in the history of the Signal

Hill oil field.

Hancock Fire

Many may still remember the

shattering explosions and raging flames from the Hancock Oil refinery fire on

Signal Hill in 1958. Several articles

were written about the event on the 50th anniversary of the disaster which

occurred on May 22, 1958. It was indeed a day to remember as a sea of

sticky, boiling oil streamed down from Signal Hill as firemen tried to contain

the flames to the tank farm area of the 10-acre plant. Homes for miles around –

in San Pedro, Long Beach, Wilmington, Seal Beach, Lakewood and other

communities – shook as if hit by a series of sonic booms as the explosions

continued. One resident a block away

said he heard at least 15 to 20 explosions within a five minute period.

|

| Hancock fire, 1958. |

It seemed to have started with an explosion in

the loading area of the refinery located south of the Municipal Airport and

Spring Street. The first blast tore up a

tank containing crude oil; burning petroleum gushed to the ground and quickly

spread the fire from tank to tank. Other

explosions followed in rapid succession.

Fifty workers fled for their lives; two, Woodward Langford and James

Edwards, didn't make it.

The stream of oil threatened the

airport and the Long Beach Municipal Gas Department plant with its huge storage

tanks. Fire fighters concentrated

efforts around this area to prevent further devastation. A vast cloud of black smoke spread eastward,

forcing the evacuation of Long

Beach General Hospital

After a 52-hour fight by 600

men, the Hancock Refinery fire was extinguished. However, firefighters could still see the

grotesque shapes of twisted metal though lingering ribbons of smoke. Woodrow H. Langford, 44, and James W.

Edwards, 66, lost their lives, eight were injured and property loss was

estimated to be in the millions.

The exact cause of the fire was

never determined, but it happened at the same time that rumors surfaced that a

large eastern oil company was interested in buying the company.

Reported accidents from the Signal Hill field include:

·

September 2, 1921, a fire occurred as the well

was being drilled at Shell’s Mesa No. 1 well. No one was injured but tools and

a rig were destroyed with a loss of $12,000.

·

November 17, 1921, asbestos clad expert

firefighters were called in to dynamite the blaze at Shell’s Martin #1 well. A

column of blazing gas shot 150 feet into the air and scattered thousands of

grains of sand for miles around. Adjacent wells and derricks were also

destroyed. Damages of $24,000.

·

December 14, 1921, the third fire in four months

at Shell Oil Co. resulting from gas escaping from newly dug Wilbur #1 well. Damages $20,000.

·

May 9, 1923, carelessness in turning on a gas

valve to a connecting line was listed as the cause of the blaze near Orange

Avenue. No damage estimate given.

·

May 27, 1923, a fire destroyed a derrick at

Shell’s Alamitos No. 7 well on Obispo. Damages $50,000.

·

July 10, 1923, a 500 gallon tank of the Gilmore

Refining Company threatened to spread downhill into Long Beach threatening

homes. $150,000 in damages.

·

October 15, 1923, fires destroy two wells on

Arabella Avenue, two firemen injured. Damages $25,000.

·

April 21, 1924, three absorbing towers and the

engine room of the Golden State Refinery on East Hill Street were destroyed

when fumes from a gas pipe ignited.

$35,000 in damages.

·

May 10, 1924, explosion and fire destroyed the

derrick and equipment on Fry #2 well at Freeman Street and Summit Road. Two die – Frank Guisinger and J.F.

Bownds. Third victim, George

Stubblefield also injured.

·

June 20, 1924, four workmen (Thomas Watson,

Everett Johnson, A. A. Cochran, J.B. Rose) on the Patton-Shore #2 well on

California Street are hurt when a drill pipe falls.

·

July 6, 1924, fire razes Betz oil derrick.

·

July 15, 1924, Fisher fire. See article in this

blog.

·

August 6, 1924, waste oil which had been

accumulating for several months in a gully north of Sunnyside Cemetery caught

fire from a spark from a welding gun.

For a time the Lomita Gas Company was threatened by the grass fire which

spread quickly. No damage estimates.

·

October 3, 1924, flames from a welding torch

started an explosion which destroyed 9 storage tanks of the Hursh Refining

Company, 19th and Rose Avenue. Damages $25,000.

·

October 23, 1924, a fire and two explosions

occurred at the absorption plant of the Pan-American Refining Company on the

north side of the hill at Arabella and Temple. Harry Perry was killed. Approximately $50,000 in damages.

·

November 27, 1924, two fires, one resulting from

an explosion. The Davis-McMillan well at Orizaba and Summit was the most

destructive which resulted when a spark of unknown origin ignited gas in the

hole. A sump hole filled with waste oil on Spring, west of American (Long Beach

Blvd.), was the scene of the second blaze which was started by a grass

fire. Theodore Deihl seriously hurt in

first fire. $20,000 in damages to the

first fire little lost in the second.

·

January 13, 1925, two badly burned in refinery

explosion.

·

February 19, 1925, spectacular fire razes

derrick on Signal Hill; blaze is seen on all roads into Long Beach.

·

February 23, 1926, the presence of a tremendous

gas field was found after the eruption of a series of wells in a new area of

drilling in the Los Cerritos area in the northwest edition to the original

field. Coombs #5 well was the first to explode (2/22/1926), with others

following. Damages to the Coombs well

was estimated to be in excess of $50,000. Five workmen injured (J.J. Biller,

A.B. McMillan, D.B. McCutcheon, J. Morean, Dewey Davis). Firemen William Minter

and Fred Campbell also injured.

·

March 25, 1926, Wilbur-McAlpin-Craig #3 well

shoots out jet of fire, crew dynamites well in effort to stop blaze.

·

June 5, 1926, one overcome, two hurt in gas

flames as derrick burns on Signal Hill.

·

May 29, 1927, seven burned in explosion at

Alamitos Heights, blast shakes J. Paul Getty derrick.

·

June 26, 1927, five wells were destroyed from a

blast and fire from the Julian Petroleum Corporations Fuller well no.1 at

Colorado and Flint. Losses estimated to be $1 million.

·

October 19, 1927, spectacular oil blaze menaces

field, Julian derrick destroyed by fire.

·

February 10, 1928, a refinery explosion kills Ray

Thompson at a Signal Oil plant at Atlantic and 32nd Street. Damages estimated to be between

$200,000-$300,000.

·

February 11, 1928, the second of two refinery

explosions within two days of each other destroyed the California Petroleum

Company’s absorption plant. Damages $50,000.

·

August 5, 1929, fire destroyed 4 oil derricks in

the Bixby Heights section of the Signal Hill oil field belonging to the

Macmillan concern. Damages $16,000.

·

August 19, 1929, two gas trucks exploded at the

Rio Grande refinery on Reservoir Hill. Fifty foot columns of fire erupted into

the air and the fire spread downhill threatening homes. Carl Bonner seriously

injured.

·

November 26, 1929, five derricks and ten oil

tanks were destroyed in an explosion which threw boiling oil over the tank

farm. The fire originated when a storage tank of the Conductor’s Oil Company

overheated and steam allowed seepage of oil which was ignited by a boiler. One

man, Fred Strong, injured. George F. Storey dies. Damages $50,000.

·

December 4, 1929, brothers Lynn and Dean Titus

were killed when fumes from an empty

crude oil tank ignited a fire at the General Petroleum Fulton McKee well #1

(Long Beach Blvd. and Pepper Drive). Two others were also injured. Loss was

minimal.

·

December 12, 1929, spectacular fire hits Signal

Hill, but loss is light.

·

May 11, 1930, three wooden derricks (Foster well

#65, Featherstone & Preston #8, Bolsa Chica #4) and two 15,000 gallon tanks

went up in smoke. The fire was on Lovelady Avenue between Willow and

Burnett. $25,000 in damages.

·

August 2, 1930, four were injured in an

explosion at the Olympic #15 well of the Western Oil and Refining Company.

Friction was said to be the cause. Damages minimal.

·

August 26, 1930, huge derrick topples in flames,

blaze caused when fumes of tank are ignited by a nearby boiler. Damages

$50,000.

·

September 17, 1930, an explosion of a tank of

crude oil at the Macmillan-Wellman lease, Locust and Pepper Drive, started a

fire which threatened the Los Cerritos section of the Signal Hill oil field.

$6,000 in damages.

·

August 7, 1931, fire damages Los Cerritos oil

well; explosion of gas picket blamed. Damages $5000.

·

December 28, 1931, occurred at the

O’Donnell-Slater well no. 1 in which two 75,000 gallon storage tanks caught

fire. $5,000 in damages.

·

October 1, 1931, wind and lightning do heavy

damage; east Coyote field suffers when electric flash strikes tank farm.

Damages $35,000.

·

June 11, 1932, a large pool of waste oil was

ignited by a grass fire in an area known as “Frog Pond.” No major damages, but the smoke enveloped the

area, blocking the sun for miles around.

·

October 4, 1932, a fire destroyed the Masters

and Daniel #1 derrick. A small explosion ignited the blaze. $5000 in damages.

·

June 2, 1933, Richfield fire. See article in

this blog.

·

November 23, 1935, an explosion, probably caused

by an accumulation of gas ignited by friction, seriously injured five men at

the M and M well #1 near Burnett and Orange. Damages not reported.

·

December 11, 1938, bursting from a refining

tube, barrels of scalding oil sprayed a small platform of the Hancock Oil

Refinery bringing a flaming death to 3 workers: Homer Huffman, William Hill,

Walter Rohrig.

·

May 24, 1939, J.W. Browder was burning grass off

a lot he owned on Signal Hill when the fire sped, destroying the engine house

and derrick of the Jamesco #5 well at 36th and Elm. Damages $5,000.

·

March 30, 1943, a fire started in a pump engine

room and damaged the E.B. Campbell well #4 derrick at Obispo and Pacific Coast

Highway.

·

July 27, 1943, an explosion of a retort at the

Comet Oil Company refinery at 2930 Cherry Avenue caused $1,000 in damages.

·

October 5, 1945, Harold Rogers was atop a

dehydrator tank at the Cree lease on Signal Hill when it blew up. Fire did not

erupt, but Rogers was killed when he was hurled 750 feet. Damage minimal.

·

January 4, 1946, a fire at Ansco Construction

Company, 23rd and Walnut, destroyed an asphalt tank and damaged heating

equipment at the road oil plant. Damages not reported.

·

July 31, 1946, two derricks and other equipment

were destroyed in an oil well fire at Miller #1 and #2 wells in the 3500 block

of Pacific Avenue. Damages $10,000.

·

January 26, 1947, a fire of unknown origin broke

out at the Hancock Oil Refinery at 28th and Junipero. No report on damages.

·

December 17, 1947, a fire originating in a well

on the Signal Oil & Gas lease on Willow between Cherry and Walnut, leaped

to two other derricks and two storage tanks. Damages $15,000.

·

May 3, 1948, oil rig fire at 635 E. Wardlow.

·

September 6, 1948, oil storage tank blows up at

31st and Long Beach Boulevard.

·

September 23, 1948, oil well on the crest of

Signal Hill, known as Brown & Stack #1, erupted mud and oil as a crew

worked puling its casing.

·

February 2, 1950, an S. D. Coates-Tailor oil

derrick fire erupted at Atlantic and 29th Street. Damage estimated at $5,000.

·

May 3, 1950, sparks from a drive belt started a

fire in the Trinity Oil Company pumping well at Alamitos Heights. Damages $2,500.

·

July 20, 1950, the Emperor derrick and pump

house were destroyed by fire. Damages $10,000.

·

July 10, 1951, the friction of a belt started a

blaze at the Apex Oil Company property at 2450 Gundry. $10,000 in damages.

·

November 11, 1951, Exeter Oil Company pumping

well set ablaze. Well located at 23rd and Junipero. Fire started in the belt

house.

·

May 10, 1952, the top of the incinerator at

Envoy Petroleum Refinery at 1601 E. Spring blew off when oil coming through the

vapor line ignited. Firefighter Lawrence Elder burned. Damages $5000.

·

April 4, 1953, oil from a broken line spilled

onto a superheating flame in a retort at the Cal-State Refinery, 2930 Cherry. $10,000-$15,000 in damages.

·

August 8, 1954, wind-swept flames engulfed three

oil derricks and threatened others when friction from a slipping belt caused a

fire. No estimate of damages.

·

March 28, 1955, fire in oil well near 2817

Gaviota. Timbers snapped power lines, narrowly missing storage tanks.

·

October 15, 1955, a fire originated at the

Hancock Oil Refinery, 2823 Junipero, when a hot oil line broke and fumes

ignited a fire. Damage minor, but Fenton Oveson injured.

·

March 27, 1957, fire engulfed an 80 foot derrick

of the Coast Supply Company’s B & H well #2. Blazing timbers snapped a

power line and caused a transformer to explode. A brush fire was also

ignited. Damages $15,000.

·

May 22, 1958, Woodrow H. Langford and James

Edwards die in the Hancock Fire. See article in this blog.

·

December 16, 1958, an oil well fire completely

destroyed an 80-year-old wooden derrick and threatened five 500 barrel tanks

full of crude oil. Cause and damage estimates not given.

·

November 5, 1959, a broken oil line caused a

spectacular fire at the Calstate Refining Company, 2930 Cherry. Damages not

provided.

·

March 20, 1960, friction of a slipping pump belt

caused a fire at Brighton Petroleum on the SW corner of Willow and Orange. $6,000 in damages.

·

December 23, 1960, a friction spark from a

Victory Oil Company well set fire to a 20,000 crude oil storage tank nearby. $15,000-$20,000 in damages.

·

December 26, 1964, an explosion and fire in a

waste oil sump ignited crude oil in five storage tanks of the MacMillan

Petroleum Corporation. The blaze was started either by a spark of an electric

motor or an overheated steam line. Damage minimal.

·

May 17, 1969, pipeline rupture permits 150

barrels of oil to bubble to the surface at DeForest Avenue and 27th Street.

·

December 1, 1980, an ARCO oil pipeline ruptured

at Gale and 28th Street. Two, Robert Davis and Richard Nieto, were

injured. A newly hired operator failed

to open two valves on the pipeline resulting in excessive pressure, rupturing

the line. Nine homes destroyed. Damages $600,000. Accident resulted in stricter

oil pipeline regulations.

·

September 10, 1986, Michael Miller and Michael

White were preparing to weld a heater at the MacMillan Oil Co. refinery when

the blast occurred. The fire was quickly contained and did not spread

to an adjacent Walnut Avenue elementary school. Cause of the fire was

not immediately known and no damage estimate was available.

·

November 24, 1992, a 20,000-gallon tank containing

unrefined gasoline exploded at the Petrolane Co. plant, 2901 Orange Ave, which

processes natural gas for sale primarily to the Long Beach Gas Department.

Estimate of damages not given.

Fatalities:

·

August 16, 1922, an explosion at a Signal Hill

oil refinery kills John K. Sligh.

·

March 6, 1923. While employed as a derrick man

on the Jergins-City lease Paul Wright slipped and fell into a hot mass of mud.

He died several days later.

·

June 2, 1923, C. Thomas Lavender killed when a

well cable snapped striking him across the back.

·

September 19, 1923. Paul F. Robinson was caught

in the catline as a joint drill pipe was being tightened and he was jerked into

the cathead and crushed before the tension of the rope could be released.

·

September 22, 1923. Andrew Daly crushed under a

fallen iron pipe. He was instantly killed when a load of well casing slipped.

·

December 11, 1923. Edward Wood was struck in the

face as the drum on the Bolsa Chica well #3 hurled through the air hitting Wood

and killing him immediately.

·

February 19, 1924. G.W. Richards killed at the

Wadolene Refining Corporation at Cherry near Anaheim in a refinery blast.

·

May 10, 1924, explosion and fire destroyed the

derrick and equipment on Fry No. 2 well at Freeman Street and Summit Road. Two die – Frank Guisinger and J.F.

Bownds.

·

October 23, 1924, Harry Perry killed when a fire

and two explosions occurred at the absorption plant of the Pan-American

Refining Company on the north side of the hill at Arabella and Temple.

·

February 11, 1927, H.L. Ward killed in fall from

derrick.

·

February 10, 1928, a refinery explosion killed

Ray Thompson at a Signal Oil plant at Atlantic and 32nd Street.

·

July 22, 1928, Forrest Glenn Penney crushed by

engine backfire at Standard Oil plant.

·

November 26, 1929, George F. Storey dies when five

derricks and ten oil tanks were destroyed in an explosion which threw boiling

oil over the tank farm.

·

December 4, 1929, brothers Lynn and Dean Titus

were killed when fumes from an empty

crude oil tank ignited a fire at the General Petroleum Fulton McKee well #1

(Long Beach Blvd. and Pepper Drive)

·

June 2, 1933, Richfield oil fire. Ten killed Robert

Bennett, Carl Robinson, Lottie Carlyon, Marilyn Carlyon, Ollie V. Jones, Duke

Gaughan, Ed Weiler, C.J. Brown, Charles Cope, and J.L. Shumway. See article in

this blog.

·

February 23, 1937, GeorgeT. Hinds is blown to

pieces as dehydrator in oil field blows up. December 11, 1938, bursting from a

refining tube, barrels of scalding oil sprayed a small platform of the Hancock

Oil Refinery bringing a flaming death to 3 workers: Homer Huffman, William

Hill, Walter Rohrig.

·

October 13, 1944; Darrold W. Peterson killed

climbing oil derrick.

·

May 22, 1958, Woodrow H. Langford and James

Edwards die in the Hancock Fire. See article in this blog.

·

February 28, 1986, funeral held for refinery

blast victim James Broadway.

·

April 3, 1986, two die as pipe breaks at a Long

Beach oil island, Steven Linn and Stephen Lowe.

NOTE 1: Accidents and reports of

fatalities became so common they were no longer covered by the press. Many of

the fatalities reported here were gathered from obituaries (1880-1923) with

were indexed by Long Beach Public Library staff. There were undoubtedly more.

NOTE 2: The Long Beach Collection at

the Main Library has maps, reports, etc. on oil wells in Signal Hill and Long

Beach. The library’s Petroleum

Collection only has non-Long Beach related items.

Claudine Burnett

August 2018